X-Ray Orchid: Where Science Meets Art

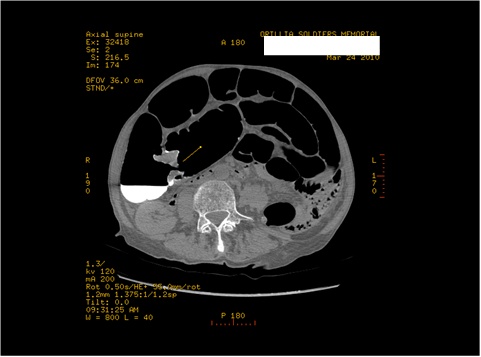

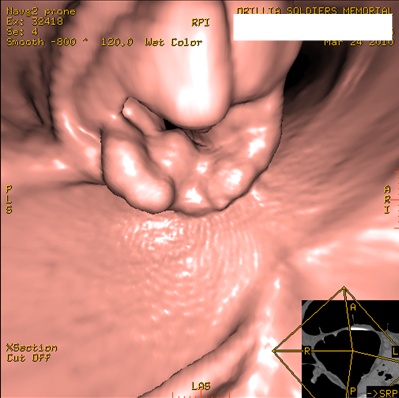

I took a picture of an orchid with a faxitron (a small, microwave-sized x-ray machine). Then I colorized it in post processing.

This project explores the hidden beauty within nature through the intersection of medical imaging and botanical photography. Using a faxitron—a precision x-ray imaging system typically employed in medical diagnostics—these images reveal the intricate internal architecture of orchids that remains invisible to the naked eye.

Each radiographic capture exposes the flower's delicate skeletal framework: the density variations in petals, the complex vascular networks, and the sophisticated structural engineering that supports these elaborate blooms. The scientific precision of x-ray imaging unveils a completely different perspective on familiar botanical forms.Through careful post-processing, the monochromatic radiographic data is thoughtfully colorized to reflect the natural hues of the orchid specimen. This artistic interpretation bridges the clinical objectivity of diagnostic imaging with the organic beauty of the living flower, creating a unique visual dialogue between scientific documentation and aesthetic appreciation.

I hope that the resulting images offer viewers a rare glimpse into the unseen complexity of nature—transforming medical imaging technology into a tool for artistic discovery and revealing the extraordinary architecture hidden within ordinary beauty.

Please consider submitting your medical-related art – photo, paintings, drawings, poetry etc to this site to share with your colleagues.