00;00;11;19 - 00;00;39;08

Welcome to Inside Radiology: A Primary Care Perspective. The primary podcast where we explore the world of radiology and its applications in primary care. I'm your host, Dr. D'Arcy Little, a radiologist and primary care physician with a passion for leveraging radiology imaging to provide optimal patient care. In today's episode will lay the foundation by understanding the importance of radiology in primary care and exploring its various applications.

00;00;39;26 - 00;01;05;07

Let's dive in. Radiology is an essential component of modern medicine, playing a crucial role in the diagnosis, the management and the monitoring of various medical conditions. As primary care physicians, we encounter a wide range of patient cases, and having a solid understanding of radiology can significantly enhance our ability to provide accurate and timely care. So why is radiology important in primary care?

00;01;05;23 - 00;01;42;07

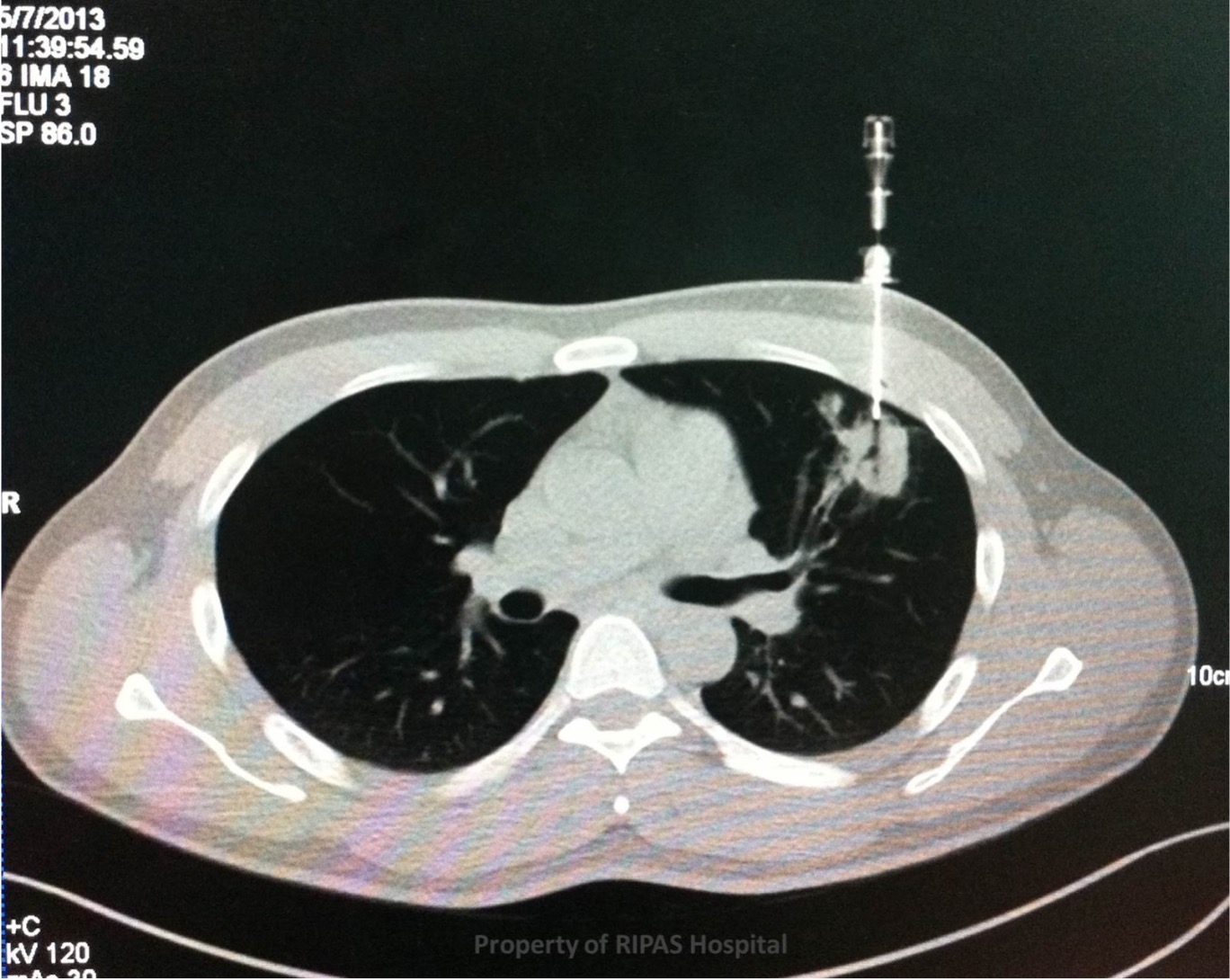

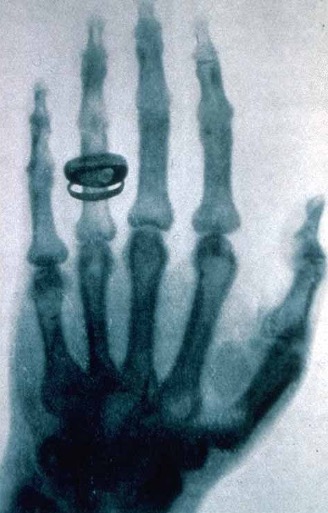

Well, imaging studies such as X-rays, ultrasounds, CTs and MRIs allow us to visualize internal structures, identify abnormalities and guide our clinical decision making. By incorporating radiology into our diagnostic process. We can gain valuable insights and often avoid unnecessary referrals to specialists. In primary care one of the most commonly encountered radiologic tests is the chest X-ray. It provides a wealth of information helping us to understand lung conditions, to detect pneumonia, to evaluate cardiac health, and to identify other thoracic abnormalities such as lung cancer.

00;01;42;26 - 00;02;13;10

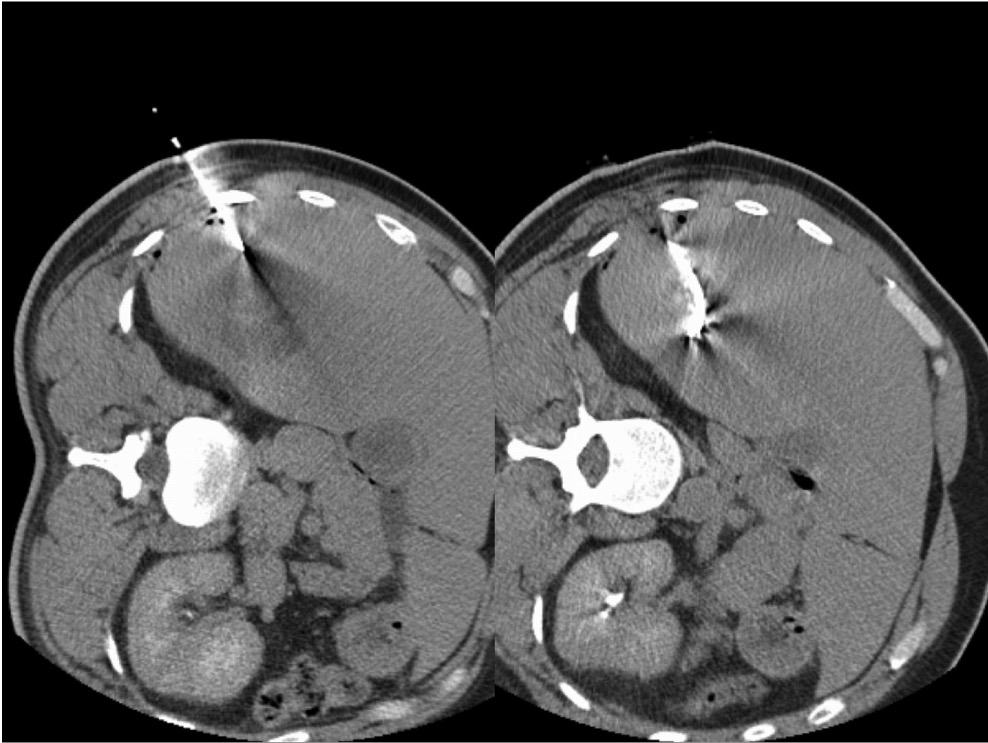

We'll explore this further in upcoming episodes. Additionally, abdominal imaging, including ultrasounds, CT scans and MRIs play an important role in primary care. They aid in evaluating abdominal pain, diagnosing gastrointestinal disorders, assessing organ health, and detecting abnormalities like tumours and cysts, and will delve further into that topic as well. Radiology is not limited to adult patients. It is equally important in paediatrics.

00;02;13;23 - 00;02;37;03

Children often present unique challenges, and understanding how to interpret and utilize radiologic studies specific to paediatric care is crucial in primary care. We will dedicate an episode to discussing paediatric radiology and common conditions we see in primary care. To make the most of radiologic studies, it's important for a primary care physicians to become familiar with the language of radiology reports.

00;02;37;25 - 00;03;08;01

These reports provide us with detailed information about the findings, impressions and recommendations of the radiologist. In a future episode will break down these reports, explain the terminology and decipher their structure to help you understanding. Now that we've discussed the significance of radiology in primary care, it's important to address appropriate utilization. Ordering the right test at the right time is essential to optimize patient care and avoid unnecessary radiation exposure and unnecessary health care costs.

00;03;08;23 - 00;03;37;18

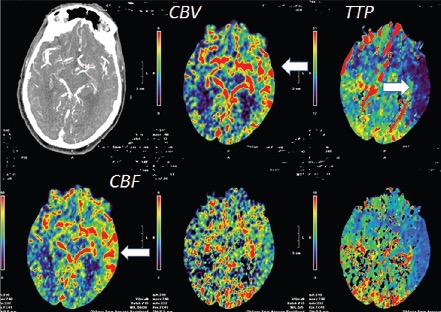

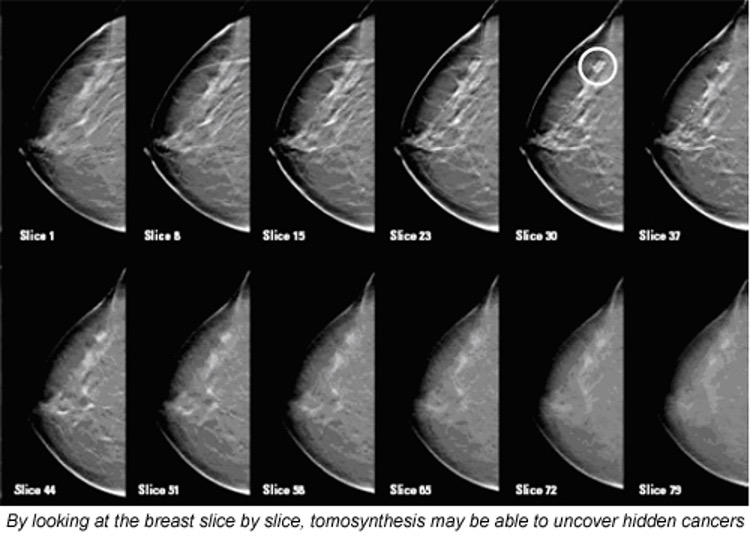

We'll explore the evidence based guidelines and appropriateness criteria in an upcoming issue. Throughout the podcast series, we'll cover a wide range of topics, including MSK imaging, neuroimaging, women's health and much more. Our goal is to equip you with the knowledge and skills necessary to incorporate radiology effectively into your primary care practice. Before we wrap up the short introductory episode, I'd like to invite you to actively participate in the podcast.

00;03;38;06 - 00;04;01;24

If you have specific questions, cases, or topics you'd like us to address, please reach out to us through our website or social media platforms to have your input. Your input will help shape the content we create and ensure it aligns with the needs of primary care physicians. Thank you for joining me today. Stay tuned for our upcoming episodes where we'll dive deeper into the world of radiology and explore how it intersects with primary care.

00;04;02;11 - 00;04;33;28

Remember, by enhancing our understanding of radiology, we can provide better care for our patients. Until next time, thank you for tuning in to this introductory episode of Primary Care Radiology. If you found the information valuable, we would greatly appreciate it if you could show your support by hitting the applause button. Remember, this podcast is dedicated to providing you with in-depth knowledge and empowering you to excel in the world of primary care radiology, to continue your learning journey, and to dive into a plethora of other fascinating episodes.

00;04;34;08 - 00;04;47;06

Be sure to subscribe below, to stay curious, stay inspired, and together, let's uncover the wonders of radiology and primary care. We look forward to sharing more captivating content with you in the future.