Anticipatory Conversations: Is there a connection to Ice Cream?

Anticipatory Conversations: Is there a connection to Ice Cream?

Diagnostic Radiology in Low Back Pain

Diagnostic Radiology in Low Back Pain

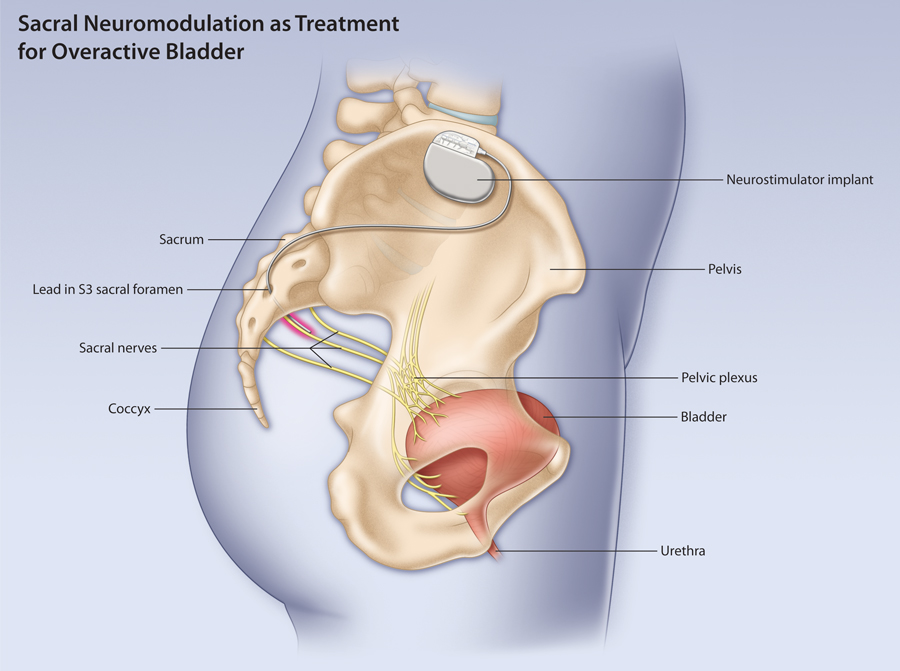

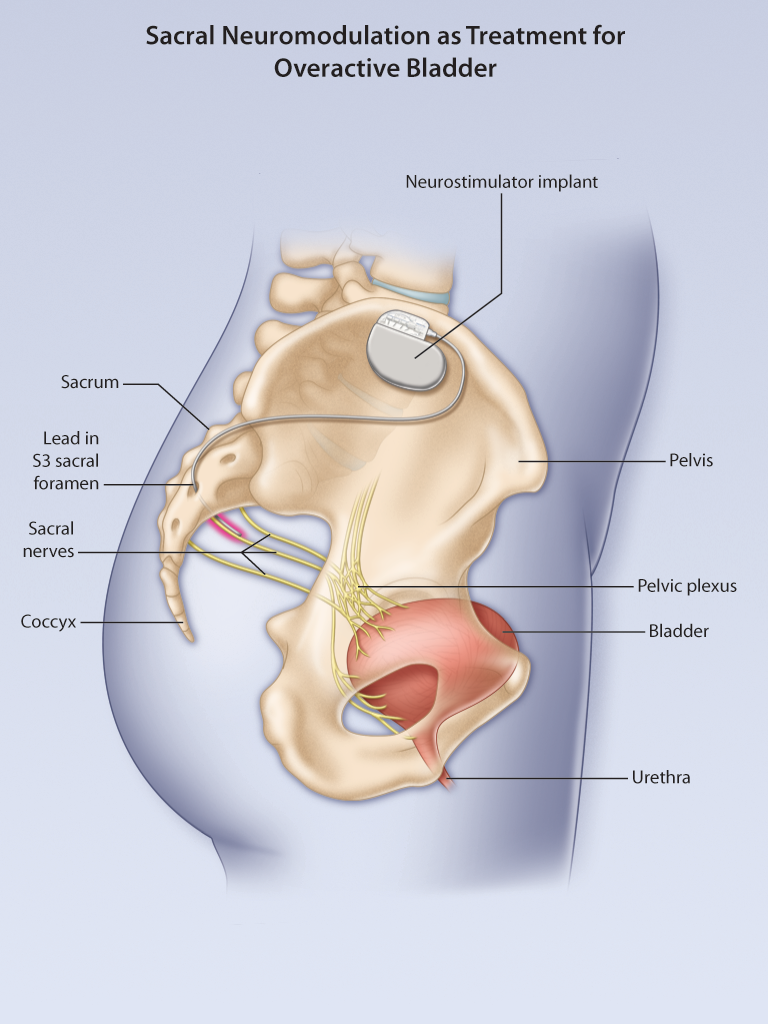

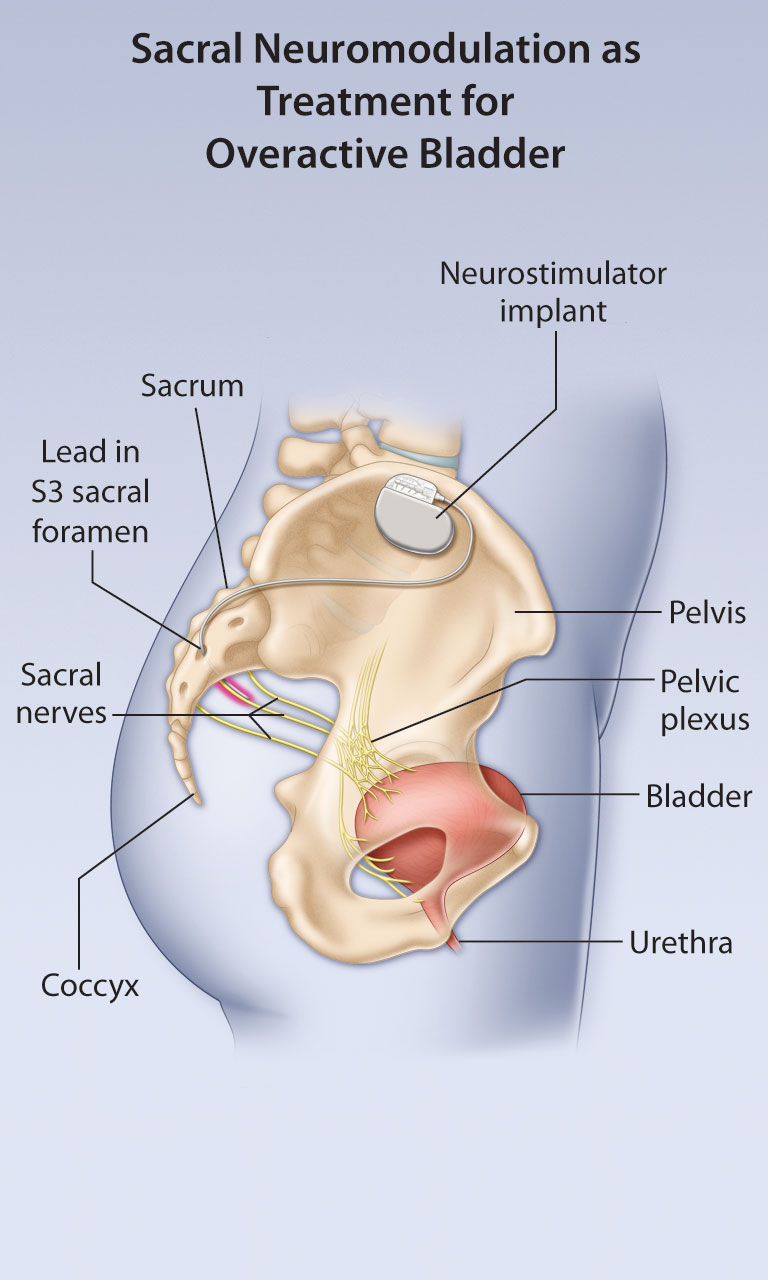

Sacral Neuromodulation for Overactive Bladder

Post-test: Sacral Neuromodulation for Overactive Bladder

Members of the College of Family Physicians of Canada may claim MAINPRO-M2 Credits for this unaccredited educational program.

| Questions | 5 |

|---|---|

| Attempts allowed | Unlimited |

| Available | Always |

| Backwards navigation | Forbidden |

You are not allowed to take this Quiz.

Pre-test: Sacral Neuromodulation for Overactive Bladder

| Questions | 3 |

|---|---|

| Attempts allowed | Unlimited |

| Available | Always |

| Pass rate | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation | Allowed |

You are not allowed to take this Quiz.

Post-test: Diagnostic Radiology in Low Back Pain

Members of the College of Family Physicians of Canada may claim MAINPRO-M2 Credits for this unaccredited educational program.

| Questions | 5 |

|---|---|

| Attempts allowed | Unlimited |

| Available | Always |

| Backwards navigation | Forbidden |

You are not allowed to take this Quiz.

Pre-test: Diagnostic Radiology in Low Back Pain

| Questions | 3 |

|---|---|

| Attempts allowed | Unlimited |

| Available | Always |

| Pass rate | 75 % |

| Backwards navigation | Allowed |

You are not allowed to take this Quiz.

Editor's Note, Volume 5 Issue 2

Editor's Note, Volume 5 Issue 2

D’Arcy Little, MD, CCFP, FRCPC

Medical Director, JCCC and HealthPlexus.NET

- Read more about Editor's Note, Volume 5 Issue 2

- Log in or register to post comments