Frank J. Molnar, MSc, MDCM, FRCPC, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) CanDRIVE Research Team, Clinical Epidemiology Program, University of Ottawa Health Research Institute; Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ottawa; Division of Geriatric Medicine, the Ottawa Hospital; REVTAR Research Group and CT Lamont Centre for Primary Care Research, Élisabeth-Bruyère Research Institute, Ottawa, ON.

Anna M. Byszewski, MD, FRCPC, CIHR CanDRIVE Research Team; Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ottawa; Division of Geriatric Medicine, the Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, ON.

Mark Rapoport, MD, FRCPC, CIHR CanDRIVE Research Team; Department of Psychiatry,

University of Toronto; Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON.

William B. Dalziel, MD, FRCPC, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Ottawa; Division of Geriatric Medicine, the Ottawa Hospital; the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, ON.

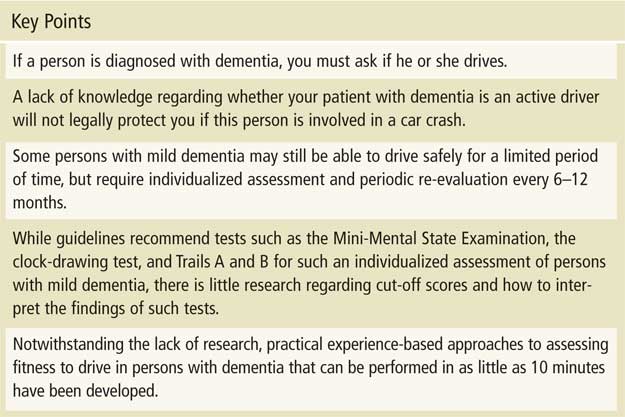

There may be up to 1.5 million persons with dementia who are driving in North America. In many jurisdictions, physicians are mandated to assess and report fitness to drive in such patients. Lack of knowledge of patients’ driving status does not protect physicians from lawsuits. There is a paucity of research to aid physicians in the assessment of fitness to drive in persons with dementia. Guidelines recommend the Mini-Mental State Examination, the clock-drawing test, and Trails A and B but lack evidence-based instructions regarding how to interpret such tests. This article provides experience-based approaches to the assessment of fitness to drive in dementia as well as an approach to disclosure of the findings to patients.

Key words: dementia, Alzheimer, driving, family physicians, cognitive testing.

Introduction

While the majority of older drivers remain safe drivers, a subset experience the cumulative functional effects of medical conditions (e.g., dementia, strokes, arthritis, Parkinson’s disease) and medications (i.e., those with sedating properties) that impact on their fitness to drive.1

In North America, there are estimated to be 3.4 million people with dementia; if the published estimated proportion of persons with dementia who are driving2 is correct, this suggests that there are more than 1.5 million drivers with dementia. In Canada, there are now an estimated 500,000 people with dementia, with an expected 250,000 new cases to be diagnosed over the next 5 years. As our population ages, the number of persons with dementia who are driving is also expected to escalate.2

In many jurisdictions front-line physicians are responsible for reporting patients who have medical conditions that may impact on fitness to drive. These legal reporting duties vary by province and territory and can be found in the Canadian Medical Association’s driving guidelines (available at www.cma.ca/index.cfm/ci_id/18223/la_id/1.htm ).3 What is less clear is how to determine which patients are unsafe to drive during assessments in front-line clinical settings (e.g., physicians’ offices).4

This is particularly true in the field of dementia. A recent systematic review revealed that no cognitive tests have cut-off scores that are validated to determine fitness to drive status in dementia.5 Consequently, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research has funded a 5 year longitudinal prospective cohort study to develop and validate screening tools for fitness to drive that can be employed by physicians in their offices (www.candrive.ca). The study will begin recruiting this year and results can be expected in 5-7 years. When such validated screening tests are available they will still need to be employed within the framework of clinically sensible approaches such as those that will be presented in this article.

Pending the results of such research, we are left to refer to consensus guidelines that, due to a lack of evidence, are largely based on individual expert opinion or the consensus of small groups of experts.3,6 Such guidelines tend to recommend tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE),7-16 the clock-drawing test, and the Trail Making Test (Trails A and B),7,16-19 none of which have well validated cut-off scores predicting fitness to drive in dementia, and some of which have conflicting published data.5 Consequently, the guidelines cannot provide evidence-based information regarding how to interpret the cognitive tests recommended (i.e., what would represent fatal errors on these tests or which validated cut-off scores to employ).5

This article presents the practical approaches that we developed for the in-office screening and assessment of medical fitness to drive in persons with dementia.4,20-22 The approaches presented in this article are based on a combination of clinical guidelines and clinical acumen and experience. They represent the attempts of seasoned clinicians to incorporate clinical guidelines into approaches that can be employed in busy clinical practices. The approaches have been refined via an ongoing iterative process of discussion and debate among us and our many clinical and research colleagues. The approaches represent our current opinions regarding the best approach to employ in this evidence-based vacuum. Consequently, readers must use their own judgment to decide how to use the approaches described in their own clinical practices.

Assessment of Fitness to Drive in Dementia

When caring for persons with dementia, it is necessary to ask if they drive. A lack of knowledge of patients’ driving status does not legally protect physicians should these patients become involved in at-fault motor vehicle crashes. To the contrary, a precedent has been set as physicians have been successfully sued when their patients were involved in crashes due to neurological conditions, even when the physicians were unaware that the patients were active drivers.23,24

Moderate-to-Severe Dementia

When cognitive impairment is so severe or obvious that it is clearly unsafe for the patient to continue driving, in-depth testing is not needed.

Mild-to-Moderate Dementia

The diagnosis of dementia does not, however, automatically mean that a person cannot drive. Some people with mild dementia may still be able to drive safely for a limited period of time, but require individualized assessment and periodic follow-up.3,6 Attempts to mandate that all persons with dementia should be forced to cease driving regardless of whether they are still safe or not, aside from being legally unsupportable, could inadvertently increase the risk to the general public. Such draconian measures could result in more people with dementia avoiding a diagnostic assessment which might thereby result in more people with undiagnosed dementia continuing to drive (i.e., patients whose unfitness to drive might have been detected during the diagnostic assessment).

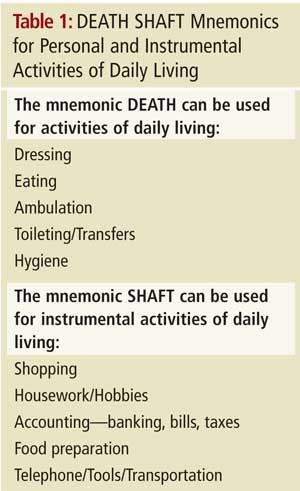

For less severe cases, clinicians need to decide if they have enough information to make a clinical decision regarding fitness to drive. The Canadian Medical Association driving guidelines3 and the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia guidelines25 indicate that persons with moderate to severe dementia should not drive, and they employ an opinion-based definition of moderate to severe dementia as demonstrating new impairments (relative to the patient’s baseline) due to cognition in one or more personal activities of daily living and/or two or more instrumental activities of daily living (see Table 1).

For less severe cases, clinicians need to decide if they have enough information to make a clinical decision regarding fitness to drive. The Canadian Medical Association driving guidelines3 and the Canadian Consensus Conference on Dementia guidelines25 indicate that persons with moderate to severe dementia should not drive, and they employ an opinion-based definition of moderate to severe dementia as demonstrating new impairments (relative to the patient’s baseline) due to cognition in one or more personal activities of daily living and/or two or more instrumental activities of daily living (see Table 1).

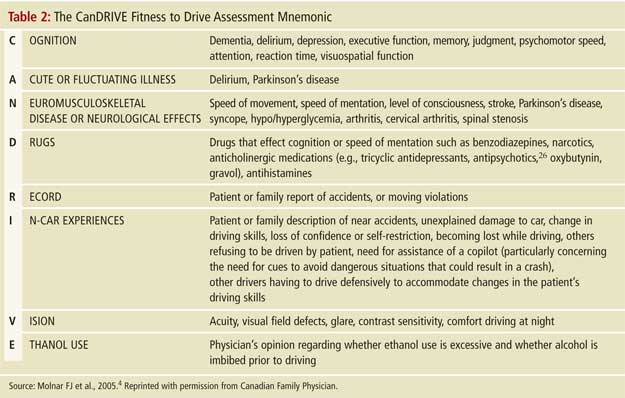

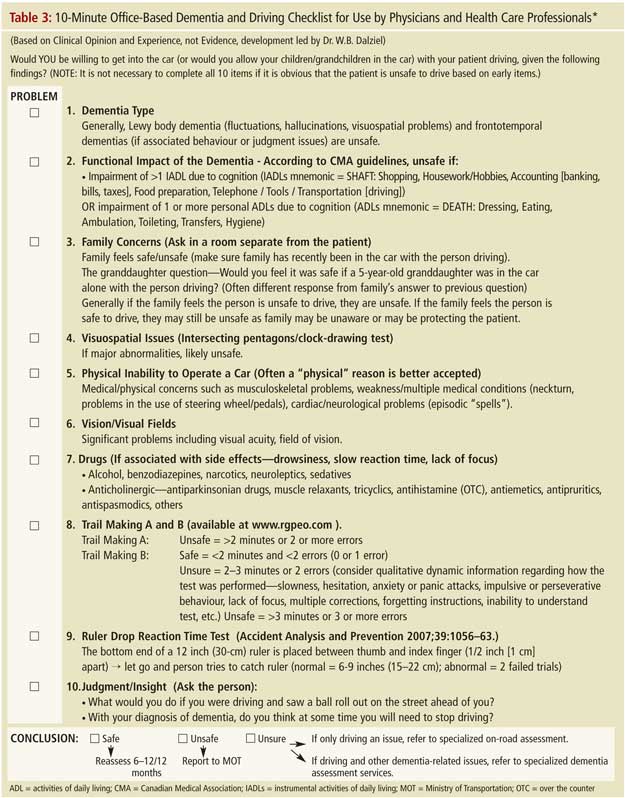

The assessment of fitness to drive in persons with mild dementia is complex and should take into account not only cognitive issues but also other medical and physical reasons indicating that they are unfit to drive. Driving cessation is often more acceptable or palatable to such patients if the decision is also based on physical (i.e., noncognitive) findings. We propose two different methods to organize the complex array of factors impacting on driving (see Tables 2 and 3). The approaches are not as lengthy to apply as they may first appear. Primary care physicians with an in-depth longitudinal knowledge of a patient will be able to answer many of the questions listed in these approaches before meeting with the patient for a more focused examination of fitness to drive. The initial elements of such a focused examination, for example, points 1-5 in Table 3, may answer the question of fitness to drive; in this case, further assessment (e.g., points 6-10, Table 3) may not be necessary. In many instances, the approach suggested in Table 3 may only take 10 minutes to complete.

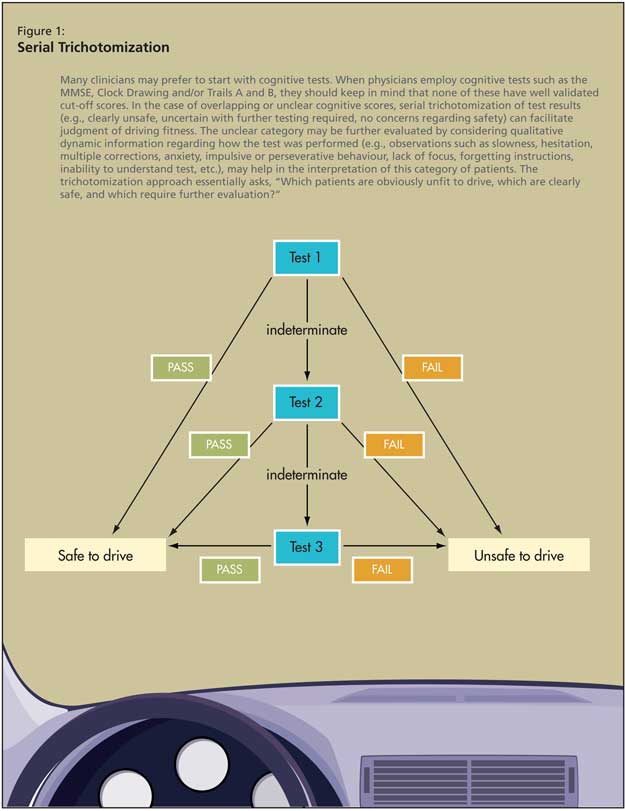

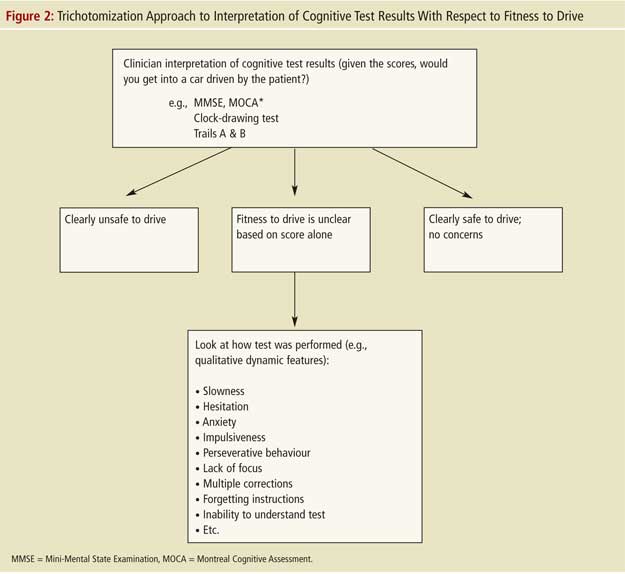

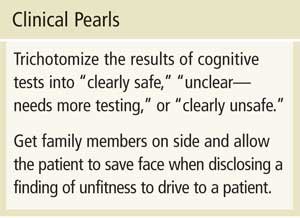

These approaches are heavily based on history and physical examination. Many clinicians may prefer to start with cognitive tests. When physicians employ cognitive tests such as the MMSE, clock-drawing test and/or Trails A and B, they should keep in mind that none of these tests have well-validated cut-off scores for persons with dementia (and when validated, such cut-off scores will likely be averages and may vary by individual). It is, therefore, recommended that clinicians use their judgment to trichotomize the results of these tests into categories of “clearly safe,” “unclear--needs more testing,” or “clearly unsafe” by asking themselves if they would get into or allow a loved one in a car that the patient is driving, given the tests results.5 As presented in point 8 of Table 3 (Trails B) and Figures 1 and 2, the unclear category may be further evaluated by considering qualitative dynamic information regarding how the test was performed (e.g., observations such as slowness, hesitation, multiple corrections, anxiety, impulsive or perseverative behaviour, lack of focus, forgetting instructions, inability to understand test, etc., may facilitate more precise judgment of this category). Given the lack of research on validated cut-off scores, and on trichotomization in general, where to set the cut-off scores remains dependent on physician judgement pending further research.5 The trichotomization approach essentially asks, “Which patients are obviously unfit to drive, which are clearly safe, and which require further evaluation?”

What to Do if Fitness to Drive Remains Unclear

If fitness to drive remains unclear after performing assessments such as those described in Tables 2-3 and Figures 1-2, then physicians should refer for further evaluation. Referral to a centre specializing in the diagnosis and treatment of dementia should be considered if there are dementia-related issues other than driving to also consider (i.e., there are insufficient resources in dementia clinics to handle large numbers of referrals purely for assessment of fitness to drive). If fitness to drive is the only issue to be addressed then referral to a centre providing specialized on-road testing would be more appropriate (in regions where such centres exist).

This recommendation comes with a caveat. In some provinces the ministry of transportation will not accept their own on-road tests as being sufficient to assess persons with cognitive impairment. Rather, the ministry of transportation requires that a more comprehensive on-road evaluation be performed at specialized ministry certified centers that are often run by occupational therapists. The high costs of these specialized comprehensive on-road tests ($500-800 to be paid by the patient in some provinces) create a barrier to the assessment and reporting of fitness to drive as they place physicians in the position of presenting patients with an ultimatum; pay for such expensive on-road tests or stop driving. This type of interaction is destructive to the physician-patient relationship and is unfair to patients of limited financial means. Systems in which patients have to pay for on-road testing discourage physicians from assessing and reporting fitness to drive and may thereby unintentionally create a risk to public safety. Some provinces such as British Columbia have addressed this by funding comprehensive on-road testing for patients with dementia if the physician recommends such on-road testing to the ministry of transportation and the ministry agrees with this recommendation. In Quebec on-road testing only costs patients $80. Ideally all provincial and territorial ministries of transportation should fund comprehensive on-road testing for persons with dementia in the way British Columbia and Quebec do. Regrettably, most ministries of transportation are not themselves adequately funded by their province to undertake this responsibility. If we, as a society, want to have safer roads then we must ask our provincial governments to better fund our ministries of transportation so they, in turn, can fund comprehensive on-road testing.

Another approach would be to consider which organizations would benefit financially from better funded comprehensive on-road testing. When people are involved in car crashes (as drivers, passengers, pedestrians, or drivers and passengers of other cars), it is the ministries of health and the insurance industry that pay the extremely high immediate and long-term costs of care and disability. The health care system and the insurance industry could potentially save tax payers and investors millions of dollars by funding comprehensive on-road testing or by sharing the costs with the ministries of transportation (i.e., a tripartite payer system including the insurance industry, ministries of health, and ministries of transportation). Such forward thinking could save both lives and money.

After the Assessment: Approaching a Person with Mild Dementia who Is Still Temporarily Safe to Drive

If a person with mild dementia is found to be able to continue to drive safely, physicians should still broach the subject of eventual driving cessation when the dementia progresses (as it inevitably will). Fitness to drive must then be re-evaluated every 6-12 months.3,29 If the clinician is concerned that the patient may not return for re-evaluation, then it would be prudent to report the patient to the ministry of transportation as “having mild dementia, but being deemed still safe to drive with re-evaluation required in 6-12 months (period for re-evaluation dependent on physician judgment).” The physician also has the option of specifying the type of follow-up required (e.g., in the physician’s office, by a specialist, or via comprehensive on-road assessment) when completing this form.

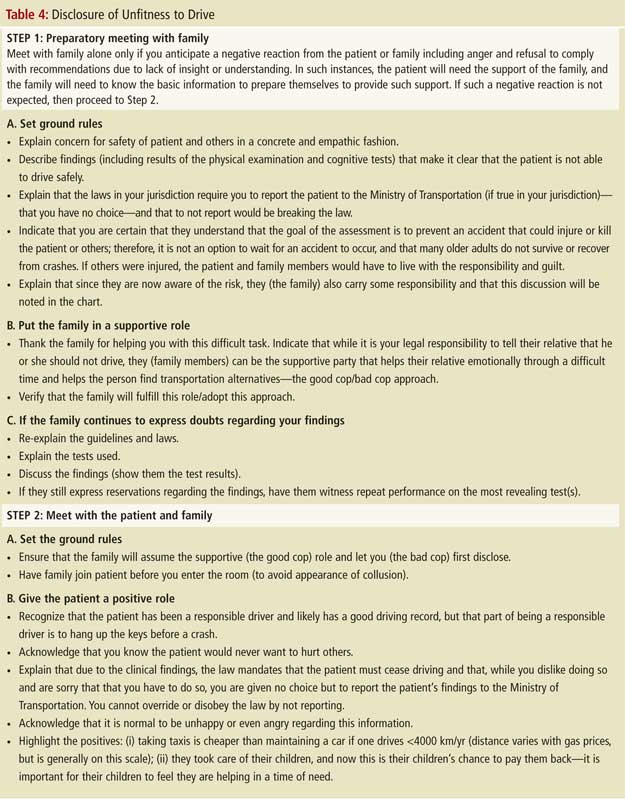

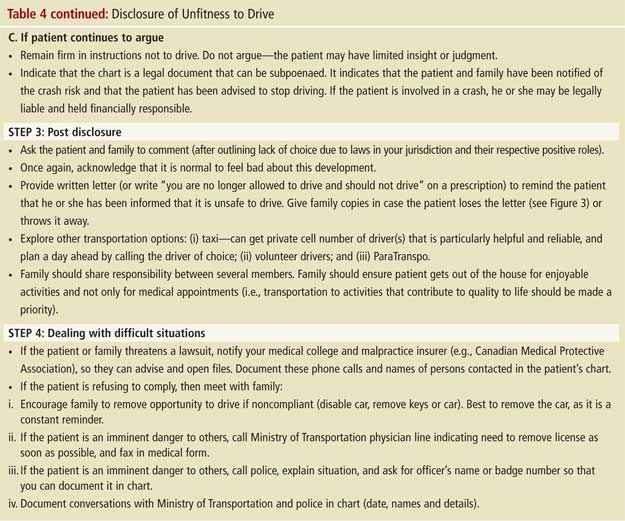

After the Assessment: Disclosing That a Person Is Unsafe to Drive

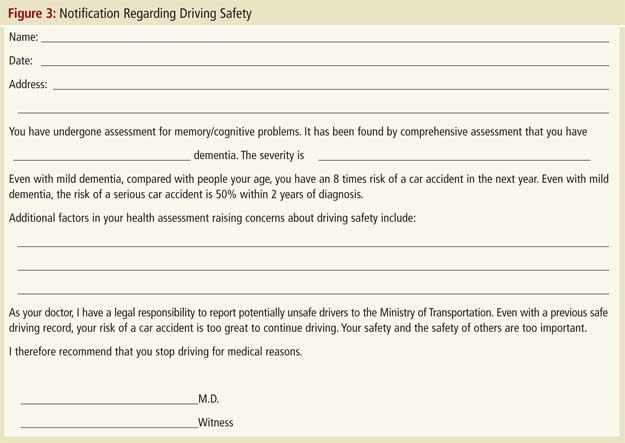

Once fitness to drive has been assessed, if the findings suggest an unacceptable risk, they must be acted on. Many clinicians find the disclosure of unfitness to drive to be a difficult, if not painful, task that fundamentally alters the physician-patient relationship. They understandably express a desire to avoid this potentially confrontational situation as they fear it will emotionally harm patients and may result in these patients, and their families, leaving their practice.27,28 As outlined in the Canadian Medical Association guidelines, physicians in most provinces are legally required to assess and report persons with dementia who are unsafe to drive.3 Even in jurisdictions where reporting is not mandated, it is still possible for physicians to be sued if their patient with dementia injures others in a car crash. Disclosure becomes unavoidable. However, as in many areas of medicine, the manner in which bad news is disclosed can moderate the negative impact on patients and families. Table 2 presents an approach that has been employed clinically by one of authors (F.M.) and that has formed the basis for presentations given on behalf of the Ontario Alzheimer Knowledge Exchange (accessible on the Exchange’s dementia and driving resource webpage at www.drivinganddementia.org ). Once a physician has disclosed a finding of unfitness to drive, it is generally prudent to also provide the finding in writing to the patient and family as the patient may forget the conversation. A sample letter is provided in Figure 3. For legal reasons, the disclosure meeting (including the date and participants’ names) should be documented in the patient’s chart.

Conclusion

By employing approaches such as those presented in Tables 2 and 3, clinicians with baseline knowledge of a patient can assess fitness to drive in a relatively short period of time and can appropriately select only those patients who truly need referral for further in-depth assessment of fitness to drive. By not referring patients whose fitness to drive can be determined in the primary physician’s office, our system will be able to better adapt to the rapidly growing numbers of older drivers who truly require specialized assessment of fitness to drive. To preserve public safety, provinces must better fund their ministries of transportation to allow these ministries to, in turn, fund comprehensive on-road testing for the escalating number of persons with mild dementia whose fitness to drive cannot be determined without an on-road test. To do otherwise will perpetuate the disincentives to physician assessment and reporting of fitness to drive described above and will place the general public at unnecessary risk.

For those interested in learning more regarding the evaluation of fitness to drive in dementia, we recommend the Ontario Alzheimer Knowledge Exchange dementia and driving resources available at www.drivinganddementia.org, and the Dementia and Driving Toolkit, available on the Regional Geriatric Program of Eastern Ontario website at www.rgpeo.com.

No competing financial interests declared.

References

-

1. Parker D, McDonald L, Rabbitt P, et al. Elderly drivers and their accidents: the Aging Driver Questionnaire. Accid Anal Prev 2000;32:751-9.

-

Hopkins RW, Kilik L, Day DJA, et al. Driving and dementia in Ontario: a quantitative assessment of the problem. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:434-8.

-

Canadian Medical Association. Determining Medical Fitness to Operate Motor Vehicles. CMA Driver’s Guide, 7th edition. (available at www.cma.ca/index.cfm/ci_id/18223/la_id/1.htm)

-

Molnar FJ, Byszewski AM, Marshall SC, et al. In-office evaluation of medical fitness-to-drive: practical approaches for assessing older people. Can Fam Physician 2005;51:372-9.

-

Molnar FJ, Patel A, Marshall S, et al. Clinical utility of office-based predictors of fitness to drive in persons with dementia: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2006;54:1809-24.

-

American Medical Association, U.S. Department of Transportation, and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Physician’s guide to assessing and counseling older drivers. Washington (DC): National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2003; http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/olddrive/OlderDriversBook/pages/I.... Accessed February 3, 2009.

-

Friedland RP, Koss E, Kumar A, et al. Motor vehicle crashes in dementia of the Alzheimer type. Ann Neurol 1988;24:782-6.

-

Lucas-Blaustein MJ, Filipp L, Dungan C. Driving in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36:1087-91.

-

Gilley DW, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, et al. Cessation of driving and unsafe motor vehicle operation by dementia patients. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:941-6.

-

Trobe JD, Waller PF, Cook-Flannagan CA, et al. Crashes and violations among drivers with Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 1996;53:411-6.

-

Rebok GW, Keyl PM, Blysma FW, et al. The effects of Alzheimer disease on driving-related abilities. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 1994;8:228-40.

-

Harvey R, Fraser D, Bonner D, et al. Dementia and driving: results of a semi-realistic simulator study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1995;10:859-64.

-

Cox DJ, Quillian WC, Thorndike FP, et al. Evaluating driving performance of outpatients with Alzheimer disease. J Am Board Fam Pract 1998;11:264-71.

-

Fitten LJ, Perryman KM, Wilkinson CJ, et al. Alzheimer and vascular dementias and driving. JAMA 1995;273:1360-5.

-

Bieliauskas LA, Roper BR, Trobe J, et al. Cognitive measures, driving safety, and Alzheimer ’s disease. Clin Neuropsychol 1998;12:206-12.

-

Fox GK, Bowden SC, Bashford GM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease and driving: prediction and assessment of driving performance. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:949-53.

-

Hunt L, Morris JC, Edwards D, et al. Driving performance in persons with mild senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc 1993;41:747-53.

-

Duchek JM, Hunt L, Ball K, et al. Attention and driving performance in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998;53B(2):130-41.

-

Rizzo M, Reinach S, McGehee D, et al. Simulated car crashes and crash predictors in drivers with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol 1997;54:545-51.

-

Byszewski A, Molnar F, Aminzadeh F. The impact of disclosure of unfitness to drive in persons with newly diagnosed dementia: patient and caregiver experiences Clin Gerontol 2009. In press.

-

Byszewski AM, Graham ID, Amos S, et al. A continuing medical education initiative for Canadian primary care physicians: the Driving and Dementia toolkit: a pre and post evaluation of knowledge, confidence gained and satisfaction. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1484-9.

-

Rapoport M, Zucchero Sarracini C, et al. Driving with dementia: how to assess safety behind the wheel. Curr Psychiatr 2008;7:37-48.

-

Capen K. New court ruling on fitness-to-drive issues will likely carry “considerable weight” across country. CMAJ 1994;151:667.

-

Capen K. Are your patients fit to drive? CMAJ 1994;150:988-90

-

Hogan DB, Bailey P, Carswell A, et al. Management of mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Alzheimers Dement 2007;3:355-84.

-

Rapoport MJ, Herrmann N, Molnar FJ, et al. Psychotropic medications and motor vehicle collisions in patients with dementia. J Am Geriatric Soc 2008;56:1968-70.

-

Marshall SC, Gilbert N. Saskatchewan physicians’ attitudes and knowledge regarding medical fitness to drive. CMAJ 1999;160:1701-4.

-

Jang RW, Man-Son-Hing M, Molnar FJ, et al. Family physicians’ attitudes and practices regarding assessments of medical fitness to drive in older persons. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:531-43.

-

Molnar FJ, Patel A, Marshall SC, et al. Systematic review of the optimal frequency of follow-up in persons with mild dementia who continue to drive. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2006;20:295-7.