D’Arcy Little, MD, CCFP, Lecturer, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto; Director of CME, Geriatrics & Aging, Toronto, ON.

The Baycrest Centre for Geriatric Care and the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto held “Psychogeriatrics Update 2004” at the Wagman Centre on the grounds of Baycrest on November 19, 2004. The morning consisted of a plenary session of particular interest to geriatric psychiatrists, community psychiatrists, geriatricians, primary care physicians, and other paramedical personnel working with older patients. This was followed by an afternoon of supplementary small group workshops. The following are some highlights from the plenary session.

Key words: psychogeriatric, bipolar, depression, older adult.

Late-Life Bipolar Disorder

The symposium opened with Dr. Kenneth Shulman’s review of late-life bipolar disorder. Dr. Shulman reminded the audience that bipolar disorder in older adults, while not a major public health problem, represents a paradigm for psychiatry in old age. This particular illness represents a complex mix of genetic, environmental, and biological factors. In addition, the treatment of the illness is often challenging because of the coexistence of other medical problems in older patients, as well as the potential for adverse drug interactions with medications such as lithium.

According to Dr. Shulman, the clinical manifestations of mania in old age are similar to those seen in patients of other ages. However, the symptoms are often not as intense as in younger patients. Furthermore, there is a higher prevalence of cognitive impairment in older adults with mania. Dr. Shulman reviewed data showing that 57% of older patients with a first episode of mania had other neurological disorders.1

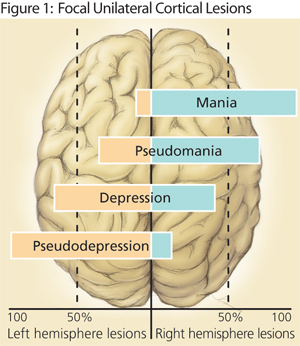

Central nervous system lesions associated with secondary mania in the aging consist primarily of right-sided lesions, especially in the orbitofrontal cortex, and are often vascular in nature. The lesions are often silent cerebral infarctions picked up as hyperintensities on CT scanning. This right-hemispheric predominance is in contradistinction to late-life depressive disorders that have been shown to have an association with left-hemispheric lesions (Figure 1).2

Central nervous system lesions associated with secondary mania in the aging consist primarily of right-sided lesions, especially in the orbitofrontal cortex, and are often vascular in nature. The lesions are often silent cerebral infarctions picked up as hyperintensities on CT scanning. This right-hemispheric predominance is in contradistinction to late-life depressive disorders that have been shown to have an association with left-hemispheric lesions (Figure 1).2

Dr. Shulman then reviewed the practical application of this data. The prevalence of vascular lesions in late-onset mania suggests important components of treatment. The initial workup of late-onset mania should include a detailed neurological exam as well as neuroimaging to detect the presence of associated neurological lesions. An important aspect of management is to optimize the treatment of other medical illnesses and to aggressively treat vascular risk factors.

Dr. Shulman then reviewed the important role of lithium carbonate in the management of bipolar disorder in the aging. This drug has the best evidence as a mood stabilizer in the older patient.3 However, its use declined with the introduction of divalproex in 1993, despite the lack of efficacy or effectiveness data in older adults. Of course, there are special considerations for the use of lithium in older patients. These include drug interactions with medications commonly used in older patients, such as thiazide diuretics, loop diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Other important considerations include altered pharmacokinetics and the possibility of altered kidney function in the older patient; in light of this, a narrower therapeutic range for lithium in the older population has been advocated, with a target serum lithium level in this population of 0.4-0.8mEq/L.

The Management of Treatment-Resistant Depression in Older Adults

Dr. Alastair Flint reviewed an approach to treatment-resistant depression in the older adult. He defined treatment resistance as the “failure to adequately improve with an adequate dose [of treatment] given for an adequate duration.” He explicated this concept by stating that treatment-resistant depression can be defined as the failure to adequately improve after two trials of two different antidepressants from two different classes with or without augmentation. Using this definition, a significant number of patients will not undergo remission. He referred to the recognition of this problem as a significant paradigm shift in psychiatry, and urged clinicians to be thinking ahead with respect to each patient with depression and their next therapeutic step(s) should remission not be achieved.

The first steps in treatment-resistant depression are to ensure that the diagnosis is correct, the patient has indeed received an adequate treatment, and that there are not coexistent medical or psychiatric disorders that are interfering with the response to treatment.

In older adults, two important coexistent disorders that need to be considered are dementia (especially frontotemporal dementia) and psychosis. For instance, an early subcortical or frontal lobe dementia can present with significant apathy and loss of motivation that can be confused with depression. In addition, the presence of psychosis is often missed and can present with profound psychomotor retardation that can be confused with severe depression. In cases of profound psychomotor retardation, Dr. Flint encouraged clinicians to consider the diagnosis of psychosis until proven otherwise. This is important because psychotic depression in older adults has been shown to be responsive to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), but much more resistant to tricyclic antidepressants or a combination of tricyclic antidepressants and antipsychotics.

Other disorders that can coexist with depression and render it less likely to respond to medication include other medical diseases such as cerebrovascular disease, dementia, and other psychiatric illnesses such as anxiety, substance abuse, and personality disorders.

Once other disorders are ruled out, a variety of strategies exist for treatment-resistant depression, including:

- Optimizing existing treatment

- Augmenting the antidepressant

- Combining antidepressants

- Substituting another antidepressant

- Considering ECT

Optimizing existing treatment can take the form of increasing the dose of medication and/or the duration of treatment to optimize the effect. Augmentation includes using other agents to enhance the success of antidepressant treatment. This can be accomplished by adding agents such as lithium (to a serum level of 0.5-1.0mmol/L), triiodothyronine (25-50µg/day), anticonvulsants, antipsychotics, stimulants (such as methylphenidate hydrochloride), or tryptophan. Lithium augmentation has the most compelling data in augmentation.

Dr. Flint reminded the audience that electroconvulsive therapy is the most efficacious treatment for depression, especially treatment-resistant depression. Important considerations here include the need to taper the ECT after a response and to start pharmacotherapy during the ECT to maintain the response.

References

- Tohen M, Shulman KI, Satlin A. First-episode mania in late life. Am J Psych 1994;151:130-2.

- Braun CM, Larocque C, Daigneault S, et al. Mania, pseudomania, depression, and pseudodepression resulting from focal unilateral cortical lesions. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1999;12:35-51.

- Bauer MS, Mitchner L. What is a “mood stabilizer”? An evidence-based response. Am J Psych 2004;161:3-18.