Optimisation des prescriptions pour les personnes âgées

Conférencier : Allen R. Huang, MDCM, FRCPC, FACP, professeur agrégé de médecine, Université McGill; directeur du service de gériatrie, centre de santé universitaire McGill, Montréal (Québec).

Le Dr Allen Huang s’est intéressé aux problèmes particuliers des prescriptions médicamenteuses aux personnes âgées.

Pourquoi les prescriptions aux personnes âgées sont-elles problématiques?

Le Dr Huang a souligné à quel point une prescription médicamenteuse de base peut s’avérer compliquée lorsqu’on a affaire à un « cas classique » de personne âgée :

Une femme de 85 ans est amenée aux urgences par son époux. Elle est confuse, souffre de nausées et de vomissements, et est très mince, ce qui correspond à un syndrome souvent appelé « détérioration générale ». Son mari signale que son état a récemment empiré, qu’elle a plus souvent besoin de son aide pour les activités de la vie quotidienne, et que sa vivacité fluctue dans la journée. La patiente souffre des troubles médicaux suivants : diabète, hypothyroïdisme, hypertension, insuffisance cardiaque congestive, fibrillation auriculaire, antécédents d’accident vasculaire cérébral et antécédent de deux décennies de polymyosite. À l’examen, elle présente une TA de 110/70 et un faible pouls de 40 battements par minute. Les épreuves de laboratoire les plus anormales incluent : RIN = 8,3; taux de digoxine sérique = 3,24 nmol/l; TSH = 0,24; clairance de la créatinine = 21 ml/min.

Elle prend actuellement 13 médicaments différents : warfarine : 2,5 mg 1 f.p.j PO; di- goxine : 0,25 mg 1 f.p.j PO; hydrochlorothiazide : 50 mg 1 f.p.j PO; lévothyroxine : 0,075 mg 1 f.p.j PO; glyburide : 10 mg 2 f.p.j PO; metformine : 500 mg 3 f.p.j PO; sotalol : 80 mg 2 f.p.j PO; alendronate : 70 mg PO tous les dimanches; carbonate de calcium : 500 mg 2 f.p.j PO; pantoprazole : 40 mg 1 f.p.j PO; gabapentine : 600 mg 3 f.p.j PO; multivitamine i : 1 dose 1 f.p.j PO; lorazépam : 1 mg PO au coucher.

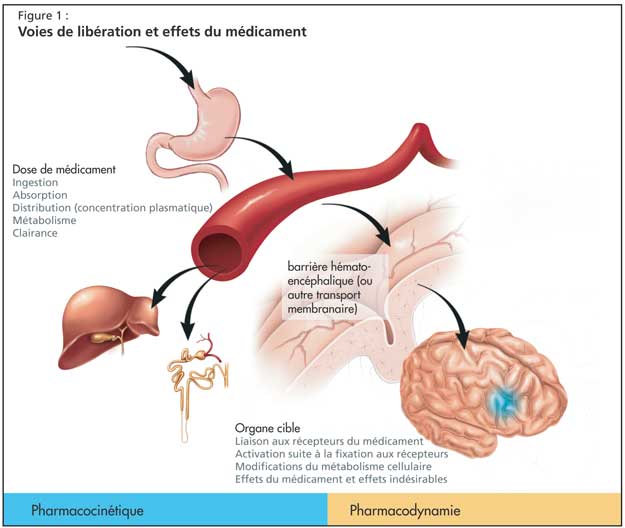

Le Dr Huang a décrit cette polypharmacie et ses conséquences comme un effet involontaire de l’approche prescriptive simple, qui consiste à identifier les troubles médicaux d’un patient et à prescrire un traitement médicamenteux classique. Cependant, les modifications des propriétés pharmacocinétiques et pharmacodynamiques des médicaments chez les personnes âgées et les multiples comorbidités observées chez ces personnes compliquent fréquemment cette approche (Figure 1).

Autres difficultés

Le Dr Huang a fait remarquer que les autres difficultés proviennent des données pharmacogénomiques et pharmacoépidémiologiques. Il a ensuite attiré l’attention des auditeurs sur les problèmes supplémentaires des maladies liées aux médicaments (en raison des interactions médicamenteuses et des interactions entre un médicament et une maladie) et sur les défis associés à la gestion de l’information depuis qu’on prescrit plus de médicaments aux personnes âgées. Il a rappelé à son auditoire que les coûts des médicaments représentent maintenant la portion la plus importante des frais de soins de santé, devant les dépenses liées à l’hospitalisation.

Le Dr Huang a détaillé les résultats d’une étude réalisée au Québec en 1990, dont l’objectif était de faire toute la lumière sur les pratiques en matière de prescription aux personnes âgées. À cette époque, le régime provincial d’assurance-maladie couvrait la totalité des dépenses en médicaments. Les chercheurs ont trouvé que le nombre de profils de prescription à haut risque (médicaments ayant une longue demi-vie, comme les benzodiazépines, ou associations médicamenteuses dangereuses, comme la combinaison d’une dose élevée d’acide acétylsalicylique et de la warfarine) augmentait avec le nombre de médecins prescripteurs et de pharmacies délivrant les médicaments. Une autre étude a montré que lorsque la province du Québec mit en place un régime d’assurance-médicaments à frais partagés, non seulement la consommation de médicaments par les personnes âgées diminua, mais cette diminution affecta parfois les médicaments essentiels, malheureusement.

Enfin, les conséquences de ces profils problématiques de prescription médicamenteuse et de consommation et d’observance du traitement de la part du patient sont davantage amplifiées du fait que les personnes âgées représentent, par définition, une population hétérogène. L’âge en tant que tel ne permet pas de déterminer correctement les conséquences des décisions pharmacothérapeutiques. En raison de tous ces facteurs, le Dr Huang a expliqué que l’optimisation de la prescription médicamenteuse aux personnes âgées représente une tâche difficile.

Optimisation du traitement médicamenteux

Le Dr Huang a noté que les médecins font face à d’autres défis dans l’exercice de leur fonction, étant souvent inondés de messages publicitaires pour de nouveaux médicaments, certains d’entre eux n’étant que des copies de médicaments existants. Nombre de ces médicaments n’ont pas été étudiés spécifiquement chez les personnes âgées, en particulier dans un contexte de polypharmacie et de comorbidités médicales multiples.

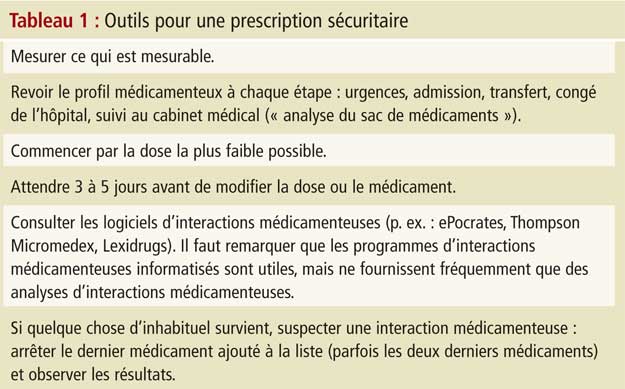

Le Dr Huang a décrit le phénomène de cascade médicamenteuse, un phénomène très important où les effets secondaires d’un médicament peuvent être interprétés de façon erronée comme une nouvelle maladie. L’ajout d’un nouveau médicament pour régler la situation (au lieu d’arrêter le médicament impliqué) peut entraîner une cascade de résultats en matière de maladies liées aux médicaments, comme dans le cas de la patiente de 85 ans présenté au début de cet article. Le Dr Huang conseille l’auditoire d’éviter les pièges liés à la prescription, en se référant à ce qu’il a intitulé les « outils pour une prescription sécuritaire » (Tableau 1).

Recommandations et conclusions

Selon le Dr Huang, il est possible d’optimiser le traitement médicamenteux pour les personnes âgées, malgré les défis décrits dans cet article. Les médecins peuvent revoir la liste des médicaments et arrêter ceux qui ne sont plus nécessaires en continu ou ceux dont le délai avant bénéfice excède l’espérance de vie du patient. Il est également utile de revoir régulièrement la liste des médicaments (en particulier lors des transitions dans les soins, comme le congé de l’hôpital), de surveiller la consommation d’alcool, de choisir des médicaments d’une même classe, mais appartenant à une autre « génération » (probablement associés à d’autres voies métaboliques) et d’utiliser des logiciels utilitaires pour dépister les interactions médicamenteuses. Il a également conseillé à l’auditoire d’éviter les médicaments ayant un indice thérapeutique limité lorsque de meilleures options existent, de s’attacher à utiliser la dose efficace la plus petite possible, et d’intégrer un plan de suivi rigoureux lorsqu’il est impossible d’éviter les interactions médicamenteuses potentielles.

Puisque tout ceci peut s’avérer un défi pour les médecins surchargés de travail, il serait bon d’envisager de partager le travail avec les autres professionnels de l’équipe de soins de santé. Par exemple, les infirmières, les physiothérapeutes et les diététistes peuvent aider à surveiller les effets indésirables médicamenteux se manifestant chez le patient sous forme de symptômes, d’hygiène orale, d’état nutritionnel, de santé et de condition physique globale et de capacité à assurer les acti-vités de la vie quotidienne. Le pharmacien joue un rôle tout aussi important, en évaluant les effets indésirables des médicaments et en offrant de la documentation sur ces effets, en suggérant des médicaments moins susceptibles d’entraîner des interactions médicamenteuses, et en éduquant le patient et la personne soignante - et peut-être les professionnels paramédicaux - sur les interactions médicamenteuses, notamment lorsqu’il s’agit d’interactions avec des suppléments, des vitamines et l’alcool.

Il est tout à fait possible de concerter les efforts et de coordonner l’action des membres de l’équipe de santé du patient, et d’optimiser un traitement médicamenteux maintenant la bonne santé et permettant à la personne âgée de fonctionner.