Évaluation de l’aptitude à conduire chez les personnes atteintes de démence

Conférencier : Frank Molnar, M. Sc., MDCM, FRCPC, membre du personnel, service de gériatrie, Hôpital d’Ottawa; professeur agrégé, département de médecine, Université d’Ottawa; chercheur affilié, Institut de recherche en santé d’Ottawa; scientifique, Institut de recherche Élisabeth-Bruyère, Ottawa (Ontario).

Le Dr Frank Molnar, membre du réseau de chercheurs interdisciplinaires du programme CanDRIVE (The Canadian Driving Research Initiative for Vehicular Safety in the Elderly), a présenté les approches pratiques permettant d’évaluer l’aptitude à conduire un véhicule dans le cadre d’un diagnostic de démence.

La recherche du programme CanDRIVE

L’équipe de recherche du programme CanDRIVE, subventionné par les Instituts de recherche en santé du Canada (IRSC), a effectué des recherches substantielles et proposé d’importantes recommandations sur l’aptitude à conduire, en s’appuyant sur une double approche. Le premier objectif du groupe fut de trouver et de valider des outils de dépistage pour cette population de patients. Ce travail fondamental a nécessité la constitution d’une équipe nationale de recherche pour examiner les aspects médicaux de l’aptitude à conduire. Cette collaboration entre divers professionnels de la santé, qui a abouti à la mise en œuvre de tests comportant des valeurs seuils en fonction des données de groupe, a permis de passer au second volet de leur objectif : faciliter le réseautage et la transmission des savoirs (aboutissant à l’ajustement des valeurs seuils et à l’utilisation de résultats spécifiques pour éva-luer chaque patient). CanDRIVE va effectuer une grande étude prospective de cohortes pour suivre les aptitudes à la conduite d’adultes atteints de démence.

Alors que la recherche primaire en est à ses débuts, le Dr Molnar a précisé que les équipes de recherche de CanDRIVE s’attacheront à transmettre les connaissances acquises aux médecins. De plus, CanDRIVE aspire à tenir compte des opinions des cliniciens sur les recherches à effectuer.

L’étendue du problème

Bien que les conducteurs âgés soient généralement plus prudents que les cohortes plus jeunes, le taux d’accidents de véhicules motorisés par kilomètre parcouru en fonction de l’âge du conducteur augmente après l’âge de 80 ans. Ce décalage, principalement dû à l’accumulation de problèmes médicaux à un âge avancé, signifie que le nombre de collisions et de victimes va prendre de l’ampleur avec le vieillissement de la population. Les salles d’urgence auront à traiter un nombre croissant de personnes âgées victimes d’accidents de la route.

Les projections de Transport Canada jusqu’en 2026 indiquent que les accidents vont surtout augmenter chez les personnes âgées. Impliquées dans un accident, ces dernières ont une probabilité quatre fois plus élevée d’être grièvement blessées ou hospitalisées, et sont plus susceptibles d’être atteintes d’une incapacité permanente ou de décéder. Elles se réta-blissent également plus lentement. Les études ont montré que la majorité des personnes âgées victimes d’accidents de la route conduisaient le véhicule, et que la plupart des accidents impliquant des conducteurs âgés mettent en cause plusieurs véhicules et touchent des innocents. Le Dr Molnar a invité ses auditeurs à considérer que ce n’est pas une faveur que de permettre aux conducteurs âgés de conduire lorsqu’ils atteignent la limite de leur aptitude à le faire sans danger.

Ce n’est pas seulement un problème d’âge

La vaste majorité des conducteurs âgés sont des conducteurs prudents, a insisté le Dr Molnar, et CanDRIVE est sensible au fait que son travail pourrait contribuer à l’âgisme ou à l’alarmisme concernant les aînés au volant. Il a souligné que les troubles médicaux et les traitements médicamenteux sont la première cause de l’incompétence des conducteurs âgés, et que tout médicament peut contribuer au risque de collision. Les personnes âgées sont affectées de façon disproportionnée en raison de la polypharmacie.

Le Dr Moldar a déclaré explicitement qu’il est impossible d’associer de manière catégorique un danger à une maladie ou un trouble chronique précis. Ce ne sont pas les troubles qui sont dangereux, mais leur gravité ou leur instabilité, auxquelles s’ajoutent des doses élevées ou les changements de doses de médicaments. Les médecins ne peuvent pas prévenir chaque accident, mais ils sont bien placés pour identifier de nombreuses personnes susceptibles d’être dangereuses au volant. Les troubles médicaux ou les médicaments qui sont les plus corrélés à une diminution de l’aptitude à la conduite sont ceux qui modifient les capacités physiques, sensorielles, mentales ou émotionnelles.

La conduite met en jeu un ensemble complexe de capacités et d’attitudes cognitives, notamment des catégories d’action opérationnelles, tactiques et stratégiques. Les médecins ne peuvent pas évaluer correctement à 100 % une fonction altérée, en raison des limites de l’examen physique (conçu principalement pour détecter la présence de maladies, et non pour évaluer la fonction ou la sécurité) et du manque de temps adéquat dans un cadre clinique de première ligne. Par exemple, les décisions prises au volant reposent sur l’aptitude des conducteurs à faire des choix tactiques, assistant les décisions contextuelles en temps réel. Si des déficiences existent dans cette catégorie, elles sont souvent difficiles à dépister par le médecin. Les médecins peuvent difficilement éva-luer la capacité stratégique, à savoir les décisions prises avant de se mettre au volant. Aucun outil de dépistage ne sera jamais entièrement efficace pour prévenir tous les accidents de véhicules motorisés. La plupart des protocoles d’évaluation ne testent que des caractéristiques intrinsèques stables de l’aptitude à conduire. Les médecins peuvent ne pas détecter une maladie récente ou fluctuante, ou anticiper le discernement de leurs patients sur des facteurs extrinsèques comme la météo, les autres conducteurs, les conditions routières ou la sécurité d’une voiture.

Évaluation clinique : survol des enjeux

On peut cependant améliorer l’évaluation, et CanDRIVE cherche à attirer l’attention sur la question, car il est bien établi qu’une altération de la fonction cognitive augmente le risque d’accident avec responsabilité pour les conducteurs. Une étude de 2004 a révélé qu’il y a actuellement des dizaines de milliers de conducteurs âgés atteints de troubles démentiels en Ontario; en 2028, ils approcheront les 100 000.

Un diagnostic de démence ne signifie pas automatiquement une interdiction de conduire, a déclaré le Dr Molnar. Cependant, un tel diagnostic signifie que le clinicien doit demander si la personne conduit encore, et la sécurité de sa conduite doit être évaluée et établie. Les exigences provinciales en matière de déclaration varient, mais elles spécifient invariablement que le trouble doit être évalué et déclaré.

Les recommandations de l’Association médicale canadienne (AMC), « Évaluation médicale de l’aptitude à conduire : Guide du médecin » (7e éd.) rejoignent les déclarations consensuelles internationales qui reconnaissent les limites des données disponibles sur l’évaluation, mais recommandent les directives suivantes : 1) interdiction de conduite pour les personnes atteintes de démence modérée ou grave (AMC : démence modérée = 1 AVQ ou 2 AIVQ altérées par un problème cognitif); 2) évaluation individuelle des personnes qui présentent une démence légère; 3) suivi périodique obligatoire (tous les 6 à 9 mois); 4) évaluation complète au volant (la norme de référence en matière d’évaluation). Le Dr Molnar a émis l’avis que les recommandations de l’AMC devraient aller plus loin en ce qui concerne les AVQ : toute altération des AIVQ dans le domaine cognitif devrait entraîner automatiquement une évaluation de l’aptitude à conduire. En outre, il trouve que la règle d’un suivi tous les 6 à 9 mois n’est pas assez flexible, et conseille une approche personnalisée (p. ex. : une évaluation tous les 3 mois dans le cadre d’une maladie évoluant rapidement).

Le Dr Molnar a attiré l’attention sur le fait que, malgré l’existence de protocoles d’évaluation clairs (comment utiliser le MMSE, le test de l’horloge, la partie B du test des tracés, etc.), aucune indication n’est fournie au médecin sur la façon d’appliquer de tels tests. Par exemple, comment réagir à différents scores, quelles valeurs seuils utiliser, et quelles erreurs constituent automatiquement un échec? Ces questions font encore l’objet de débats. CanDRIVE a examiné des douzaines d’articles sur la démence et la conduite, mais n’a pas trouvé un seul test cognitif dont l’analyse s’appuie sur une valeur seuil validée. Les cliniciens travaillent dans un vide de données prouvées.

Une approche pour évaluer l’aptitude à la conduite

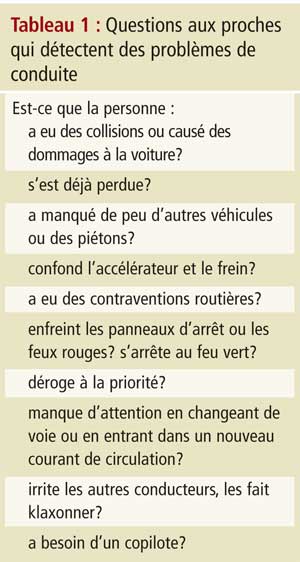

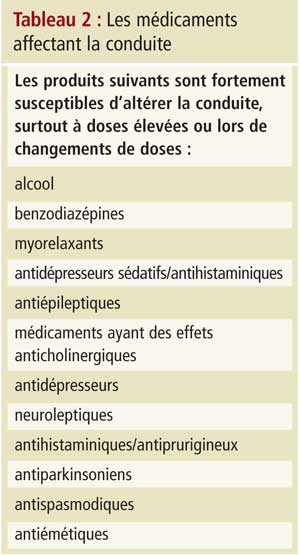

Les cliniciens doivent d’abord poser la question : « Est-ce que vous conduisez? » L’absence d’une telle vérification n’a pas protégé les cliniciens en procès, a averti le Dr Molnar. Ensuite, souvenez-vous que l’aptitude à la conduite repose sur un tableau clinique global, comprenant la cognition, le bilan fonctionnel, les capa-cités physiques, l’état de santé, le comportement et le dossier de conducteur du patient. Et puis, après les questions générales, réalisez des tests cognitifs spécifiques. Les renseignements corroborés par la famille peuvent être utiles, et le Dr Molnar a suggéré plusieurs pistes d’enquête qu’il vaut mieux aborder en l’absence du patient (Tableau 1). De plus, prenez en compte les états pathologiques qui, lorsqu’ils sont graves, mal contrôlés ou en évolution rapide, peuvent compromettre l’aptitude à la conduite (il a invité les cliniciens à se poser la question : « Est-ce que je monterais dans une voiture conduite par cette personne sur la foi de ces résultats? »). Le Dr Molnar a recommandé d’attacher la plus haute importance aux « 3 D » (démence, délire et dépression). Il a ensuite passé en revue les médicaments pouvant affecter la conduite (Tableau 2).

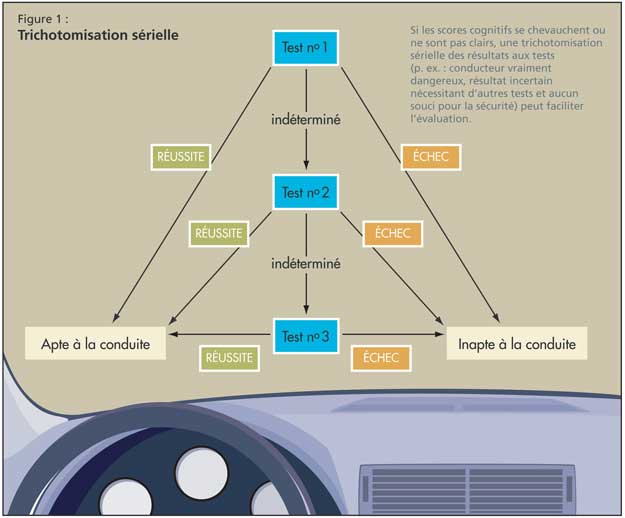

Il est essentiel de tester des domaines cognitifs spécifiques, comme le font les protocoles susmentionnés. Le jugement est apprécié par la réponse à des tests éva-luant la réaction à des situations dangereuses (comme le feu); les capacités visuo-spatiales sont testées grâce au MMSE et au test de l’horloge; la fonction exécutive est évaluée par les parties A et B du test des tracés, le test de l’horloge et le test de fluence verbale (nommer des animaux pendant une minute); et le temps de réaction peut être vérifié par le test de rattrapage de la règle lâchée. Dans le cas où les scores cognitifs se chevauchent ou ne sont pas clairs, le Dr Molnar a plaidé pour une trichotomisation sérielle (p. ex., conducteur vraiment dangereux, résultat incertain nécessitant d’autres tests et aucun souci pour la sécurité; figure 1).

Il a recommandé de commencer par le MMSE : les patients obtenant un score inférieur à 20 représentent probablement un danger au volant. Tous les tests mentionnés apportent des données précieuses; le test de rattrapage de la règle lâchée, bien que non validé, est important pour évaluer les réactions. De tels tests sont très utiles parce que les décréments du temps de réaction (qui n’est pas évalué lors de l’examen physique) ne deviennent souvent apparents qu’en dehors des tests, où les laps de temps se comptent en secondes. Néanmoins, la conduite implique des temps de réaction de l’ordre de la milliseconde.

Conclusion

Le Dr Molnar a terminé en insistant sur le fait qu’en cas de diagnostic de démence, il convient de s’interroger sur l’aptitude à conduire, et en faire une évaluation formelle et bien documentée. Les médecins peuvent effectuer une évaluation clinique approfondie de la sécurité au volant en 15 à 20 minutes. Si les cliniciens ne sont pas convaincus d’une telle sécurité, il convient d’orienter le patient vers des évaluations spécialisées ou des tests spécialisés sur route. En cas de démence, il faut réévaluer la sécurité au volant tous les 6 à 9 mois. Finalement, il a invité toute personne ayant des idées concernant l’évaluation de la conduite de les porter à l’attention du personnel de CanDRIVE par l’intermédiaire du site Web du programme (www.candrive.ca).